The Reading Well Blog 2025

What is Dyslexia

By Anne Glass / June 2025

If you're worried that your child is having a hard time learning to read or spell, you're not alone—and you’re not imagining it. Dyslexia is a common learning difference that affects how the brain processes written language. It impacts about 15–20% of children and can make reading, spelling, and writing more challenging. But here’s the good news: with the right support, kids with dyslexia can and do thrive.

So, what exactly is dyslexia?

According to The International Dyslexia Association (2002):

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

Dyslexia is not a sign of low intelligence nor poor effort. In fact, many children with dyslexia are smart, curious, and full of potential. Their brains just process language differently—especially when it comes to connecting letters and sounds, an ability called phonemic awareness.

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that affects skills like:

- Recognizing words quickly and accurately

- Spelling and remembering how words look

- Breaking words apart into their sounds (decoding)

This often shows up early—sometimes even before a child starts school. It also runs in families, so if a parent or sibling has struggled with reading, there is a greater chance your child will too. You might notice difficulty with:

- Rhyming games

- Remembering the names of letters or common objects

- Matching letters with the sounds they make

- Difficulty learning the alphabet (learning letter names or learning letter sounds)

- Mixing up sounds in words, like saying aminal instead of animal

- Trouble sounding out new words

- Slow, effortful reading

- Avoiding reading aloud or guessing at words based on pictures

- Spelling challenges

- Messy writing or disorganized thoughts when writing

- Trouble following multi-step directions

- Low confidence or frustration with schoolwork

What Causes Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is neurological, meaning it's a result of how the brain is wired. It’s not caused by poor teaching, screen time, or problems with vision or hearing. And it’s not caused by a lack of effort—in fact, many students with dyslexia work extra hard just to keep up.

What Can You Do?

- Act early. If your child is in preschool or early elementary school and struggling with reading, don’t wait. Talk to your child’s teacher or pediatrician. Ask about having your child evaluated for a reading difference. Children can be diagnosed with dyslexia as early as kindergarten or before.

- The earlier your child gets support, the better.

- Helpful Supports and Strategies:The Good News!

- Explicit, structured phonics instruction (often called multisensory or Orton-Gillingham-based approaches)

- Extra time for reading or writing tasks

- Assistive technology like audiobooks or speech-to-text tools

- Emotional support and encouragement to build confidence

- Peer support programs, such as Eye to Eye, which connects kids with mentors who have learning differences

- Children with dyslexia can learn to read and succeed. The goal of reading is understanding—and with the right tools, kids with dyslexia can develop strong comprehension, critical thinking, and communication skills.

- Dyslexia is just one part of your child’s story. Many successful adults—including authors, entrepreneurs, scientists, and artists—have dyslexia.

- If you're feeling overwhelmed, take heart: by learning more and seeking support, you're already taking the most important step.

To Sum Up:

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. Dyslexia is not a reflection of intelligence or effort. It is not caused by vision problems, hearing issues, or poor teaching. It often runs in families. Early identification and targeted interventions are key.

Final Thought:

Don’t wait. If your child is showing signs of early reading difficulty in kindergarten or first grade, ask questions. Request support and if difficulties persist, ask for an assessment. The earlier the help, the better the outcome.

For more information on reading development and what it means to “read for meaning,” check out our companion article below: What Is Reading?

What is Reading?

By Anne Glass / May 2025

If you are an adult who enjoys reading, you may be surprised how complicated reading for meaning actually is. It requires the simultaneous orchestration of phonics, oral language, and prior knowledge. It’s helpful to break down reading into a simple model:

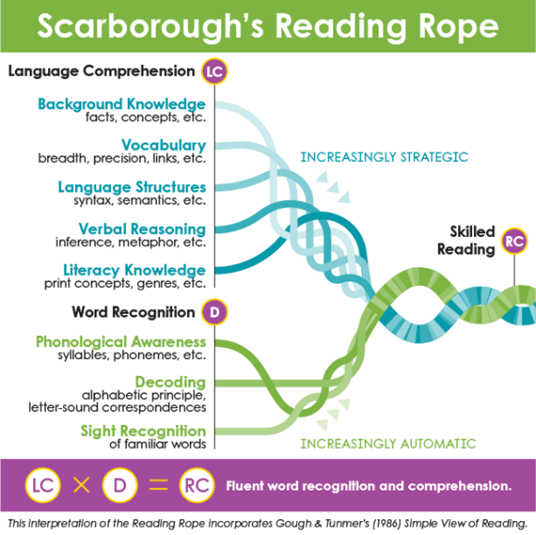

Reading = Decoding x Language Comprehension

This is the “Simple View of Reading” (SVR) originally defined by Gough and Tunmer, 1986. Under SVR, reading is the product of decoding words (identifying words accurately) and understanding those words in spoken language. Dr. Hollis Scarborough represented this model in the following ‘Reading Rope’ diagram:

Looking at this diagram, it becomes clear just how complex reading for meaning is. It involves multiple cognitive functions, including decoding, listening comprehension, and verbal reasoning. If there is a weakness in any of these intertwined ropes or skills, the process of reading can break down.

It is crucial to understand that development of skills in the top rope and the bottom rope are mutually dependent. Concurrent development will support fluent, skilled reading for meaning.

From my personal teaching experience, I would add focused attention to this diagram, which is not part of Scarborough’s otherwise thorough model.

Breaking Down Reading Skills

Decoding can be broken down into a set of subskills: phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition.

Phonological awareness is the sensitivity to the sound structure in spoken language. This includes recognition of words, syllables, and the individual sounds (phonemes) in words.

A child develops early reading skills by listening to the sounds of spoken language, learning the names of letters in the alphabet, and then mapping those sounds (phonemes) onto letters. Research shows us that phonological skills exert a causal influence on learning alphabetic reading skills, which in turn support the development of phonological skills. In other words, phonological awareness and alphabetic reading skills are mutually reinforcing.

Decoding refers to the process of translating written letters and words into their spoken equivalents. This involves using knowledge of letter-sound relationships (phonemes) and spelling patterns to sound out and recognize words. Decoding is a key skill in early reading development, helping learners to read unfamiliar words by sounding them out based on their phonetic components.

Sight recognition of words refers to the ability to recognize and read words instantly, without needing to decode them by sounding out each individual letter or sound. Put another way, these common words can be recognized instantaneously (on sight) because of their high frequency in written text. Attaining sight word proficiency requires practice.

Sight word recognition skills develop as a student encounters words frequently enough that they become stored in memory, allowing for quick recognition. Recognition of sight words is typically applied to high-frequency words and irregular words that do not follow standard phonetic patterns and cannot easily be decoded using phonics rules.

Common Sight Words

|

you said does would they friend one eight could should |

These are words that break decoding rules and should be taught as an automatic recognition task. Also, pointing these words out in connected text is very helpful, so readers can see them in context.

Children also learn the rules of syntax and grammar through conversation and listening to stories read aloud. Even without the formal knowledge of parts of speech, a child learns that subjects and verbs must agree. Students should learn to understand that there is a difference between I and me and they and them, etc. This is one of the ways oral language supports the development of written language.

Once a child is able to accurately decode words, they can begin to make sense of written text. They probably already have experience making sense of text from listening to grown-ups read aloud. Talking about stories read aloud is a very important part of developing reading comprehension. This practice develops listening comprehension, a crucial component in the Simple View of Reading. Now that they have begun to break the code of written language, they can begin to do it for themselves and make sense of stories..

For most children, the move from oral phonemic activities to mapping spoken language to print happens fairly easily, especially with the support of direct, explicit instruction. Nevertheless, for nearly 20% of children, breaking the reading code does not come easily. For struggling readers, Scarborough’s Reading Rope can be a useful conceptual tool to help identify the areas within which a student may struggle. If the area of weakness is decoding, for example, a phonics-based reading curriculum will help to improve accuracy and automaticity, thereby ameliorating reading difficulties later on.

Starting at a very young age and listening to a variety of texts helps children develop familiarity with new vocabulary, conventional syntax, learn new vocabulary, add to and/or challenge their prior knowledge (also called schema), and identify other perspectives. Listening to stories read aloud does a lot of work to prepare children to read independently!

If you find that your child has unusual difficulty breaking the phonics code to learn to read, you should definitely schedule a meeting with his or her teachers. Your child may be at risk of a lack of effective instruction, a reading disability, or dyslexia.

For more on the topic of the Simple View of Reading (SVR) from Anne, watch her How Cast video below!

Return to the top of the Reading Well Blog